Kourtney Kardashian Claps Back at Claim Kim Kardashian Threw Shade with Recent Photo You’ll flip over Kourtney Kardashian‘s birthday celebration. The Kardashians star—who

LATEST NEWS

LATEST NEWS

TECHNOLOGY

Snap says total watch time on its TikTok competitor increased more than 125%

As part of its Q1 2024 earning release, Snap revealed that total watch time on its TikTok competitor, Spotlight, increased

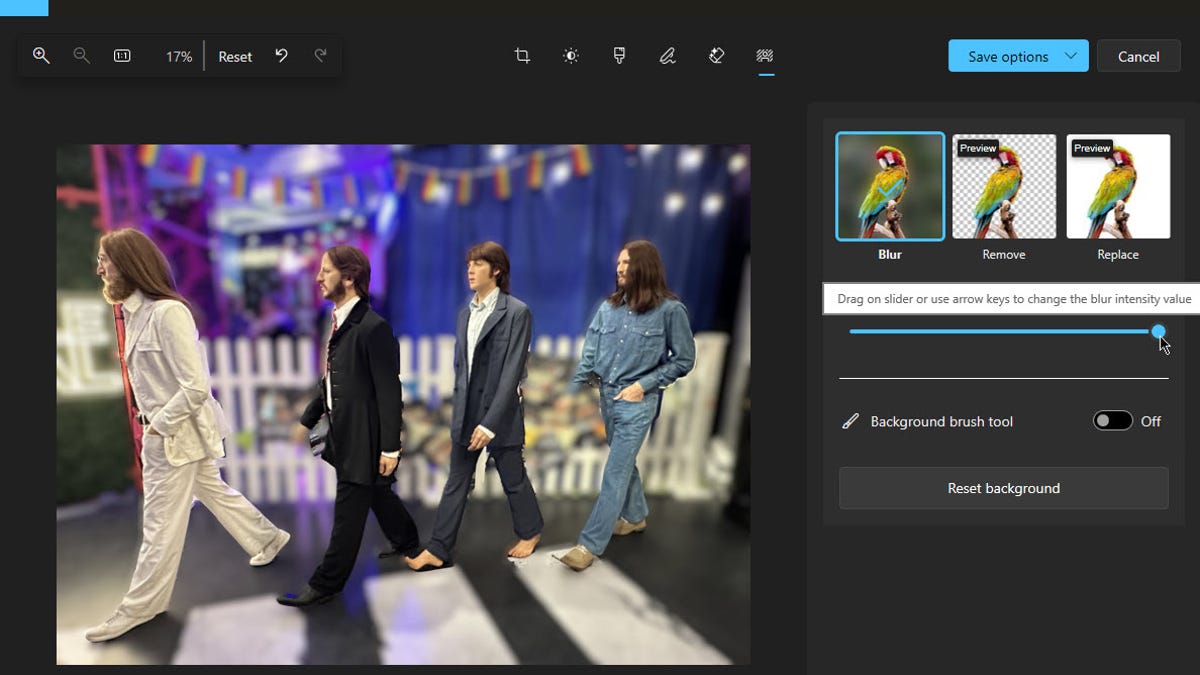

How to use AI in the Windows Photos app to change the background of an image

Screenshot by Lance Whitney/ZDNET You’ve snapped a memorable photo with your phone. There’s only one problem — you don’t like

Chilean instant payments API startup Fintoc raises $7 million to turn Mexico into its main market

Open banking may be a global trend, but implementation is fragmented. The fintech startups doing the legwork to make it

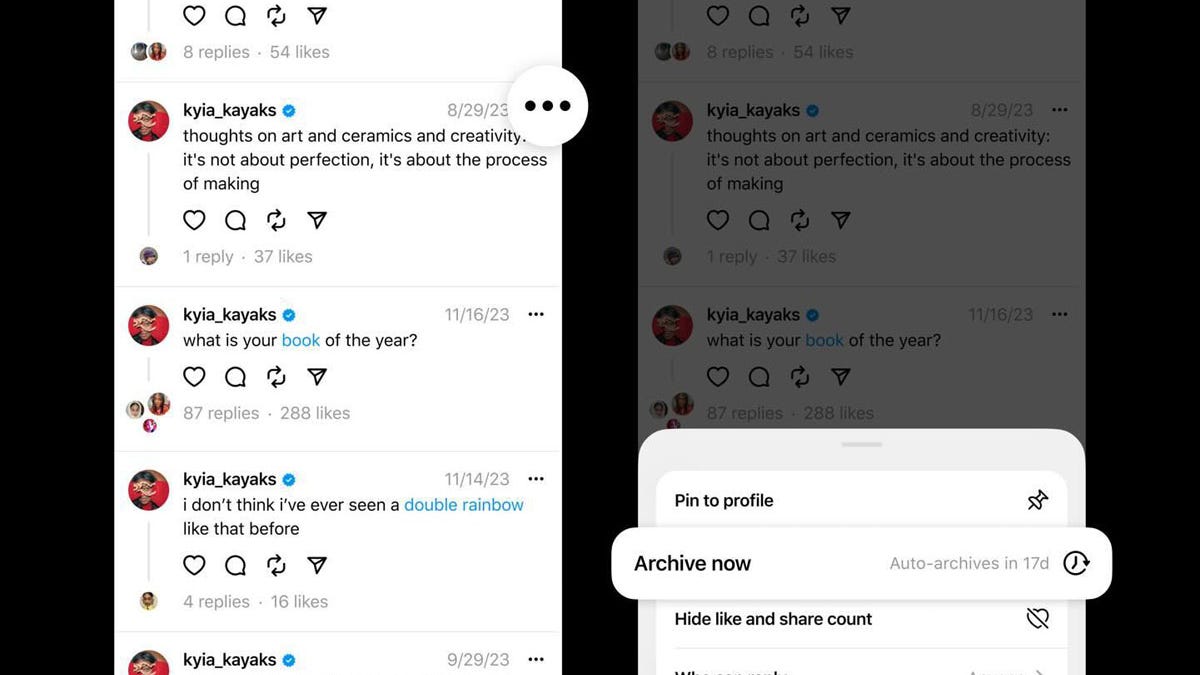

Threads tests letting you hide your public posts, as monthly users jump to over 150 million

Lance Whitney/ZDNET Meta is testing a new Threads feature that lets you archive your public posts, rendering them invisible to

Ex-NSA hacker and ex-Apple researcher launch startup to protect Apple devices

Two veteran security experts are launching a startup that aims to help other makers of cybersecurity products to up their

World

Six takeaways from Trump immunity hearing and New York hush money trial | Donald Trump News

Former United States President Donald Trump saw two of the four criminal cases against him move forward on Thursday. In